Coolships in Franconia and beyond

In the quiet attic of a Franconian brewery, a wide copper pan sits waiting under the rafters. When boiling wort is pumped in, a billowing cloud of steam fills the space, and the sweet aroma of malt and hops drifts out into the village. The brewer watches as the hot liquid spreads across the shallow vessel – a coolship – just as generations of brewers before him have done. This old-fashioned scene could be mistaken for a museum exhibit, yet it’s happening today. The coolship, a brewing tool with medieval roots, remains very much alive in corners of Franconia, even as it has nearly vanished elsewhere.

This article explores the rise, fall, and resurgence of coolships: from their origin centuries ago, through their essential role in traditional lager brewing, to their decline with industrialization, and finally their revival in Franconia and among craft brewers worldwide.

Origins of the Coolship

The concept of the coolship emerged from brewing’s most fundamental challenge: how to cool boiled wort before fermentation in the era before refrigeration. So far historians have not been able to pinpoint the exact time or place it first appeared – evidence of shallow, uncovered cooling vessels in brewing goes back at least to medieval times. In fact, the very name “coolship” (an Anglicization of the Dutch koelschip and German Kühlschiff) could hint at medieval brewers’ practices. Excavations of breweries from the early Middle Ages suggests that brewers would pour hot wort into hollowed-out tree trunks – essentially wooden troughs resembling primitive boats – to let it cool. Hence a “coolship”, perhaps. By spreading the liquid thin, they discovered it lost heat faster. It doesn’t take a physicist to grasp the idea: more surface area and shallow depth means quicker cooling in the ambient air.

Metal, usually copper or tin, equipment was extremely expensive in the Middle Ages, but slowly became more used in breweries as the industry evolved. Most important was the kettles for boiling, but one can imagine that getting coolships in copper would be next on a brewers’ investments list, as the wooden coolships would decay quicker when the wort was introduced at a higher temperature.

As brewing in Northern Europe became more organized throughout the Middle Ages and especially in the early modern period, these shallow cooling vats evolved in design. Early coolships were sometimes large tubs or troughs, but over time they took shape as wide pans, a foot or two deep, often rectangular and made of wood staves sealed with pitch. By the 18th and early 19th centuries, as commercial brewing scaled up significantly, coolships were a common fixture in breweries across Britain, Belgium, and the German principalities. They were typically installed in brewery lofts or outbuildings where cold air could circulate over the hot wort as we know them to be used today. Their practical function was and is threefold: to cool the wort, to aerate it, and to allow trub (solids and protein break) to settle out. Brewers found that as the wort slowly cooled in the open pan, it naturally absorbed oxygen from the air – a boon for yeast health in an era long before pure oxygenation techniques. The stillness of the pan also let unwanted solids and coagulated proteins (the “cold break”) separate and sink, yielding clearer wort for fermentation .

Naturely, early brewers also learned the risks that came with these benefits. An open vessel of warm, sugary liquid is an open invitation to any wild microbes floating by. Leaving wort exposed for hours meant stray yeasts and bacteria could dive in, potentially spoiling the beer. Before germ theory, brewers didn’t fully understand microbes, but through experience they knew that “souring” or infections were more likely if cooling took too long. Thus, the coolship an innovation of necessity – it cooled wort faster than leaving it in a big kettle – but it was still a race against time and microbes. Brewers in cooler climates or seasons had an edge, as cold nights would chill the wort faster and discourage bacteria.

By the mid-1800s copper or iron was the typical material for coolships which gave better durability and heat conductivity. Copper especially became favored because it transfers heat quickly (speeding cooling) and is easy to clean; many 19th-century breweries installed shining copper coolships that became points of pride.

Coolships and the Lager Brewing Tradition

The coolship’s golden age coincided with the rise of lager brewing in central Europe. This synergy was especially apparent in Bavaria and its northern region of Franconia – lands that would become famous for crisp lagers. Lagers require fermentation at cooler temperatures and long maturation, a practice perfected in Bavaria during the 19th century, but with beginnings as early as the 1400s in Southern Germany.

Historically, it was common that cities or even principalities had statutes regarding when it was allowed to brew and with what ingredients. In Bavarian, a decree of 1553 had banned brewing between late April and late September partly because the summer heat led to rampant spoilage (and mostly because it posed fire hazards with wooden equipment). Brewers thus made their beer in the cooler months, and they often harvested ice from rivers and lakes to pack their cellars for lagering. The coolship, typically located in an upper story or rooftop of the brewhouse, took advantage of the chilly winter air. On a brisk February night, a brewery could pump boiling wort into the coolship and count on the frigid air wafting through louvered windows to drop the temperature rapidly. In essence, the entire brewery became a giant heat exchanger, with the coolship’s wide surface shedding steam into the cold Franconian sky. By dawn, the wort might be cool enough (down to maybe 5–10 °C) to be drained to fermenting vessels in the cellar below. This allowed the freshly pitched lager yeast to get to work in its preferred cold environment without delay.

Franconia, a region dotted with small villages and family breweries, became a bastion of such traditional methods. Many of these breweries were slow to industrialize, holding onto older equipment well into the 20th century. It was not uncommon for a Franconian brewhouse to have a dedicated cooling room in the attic with a coolship – sometimes startling unsuspecting visitors who climbed upstairs to find a broad, gleaming “beer pool” open to the rafters. For example, Brauerei Drei Kronen in Memmelsdorf installed a new copper coolship in 1955, which they still use to cool wort for 30–60 minutes before fermentation. Even in the mid-20th century, as more modern equipment became widespread, traditional brewers in this area believed in the coolship’s value for their lagers quality. In fact, the commitment to these time-honored methods endures, as evidenced also by Rittmayer in Aisch, which installed a new coolship as recently as 2024.

As brewing science accelerated during the 19th century, inventors sought new ways to make cooling more efficient. A major breakthrough came in 1856 when French engineer Jean-Louis Baudelot introduced the Baudelot cooler, an early external heat exchanger. This device ran cold water through pipes and spread hot wort in a thin film over them, chilling the wort in a fraction of the time of a coolship. Baudelot’s innovation was driven by the reality that traditional coolships required long exposure (“easily took 8 hours”) and sometimes led to sour beer. By cooling wort “in less than a quarter of the original time needed”, the Baudelot cooler limited exposure to contaminating microbes while still aerating the wort as it cascaded over the pipes. From the late 19th century onward, many breweries adopted either Baudelot coolers or other new technologies (e.g. counterflow chillers, plate heat exchangers) to replace or supplement coolships.

A retired Baudelot cooler previously used by Brauerei Wagner in Merkendorf

A retired Baudelot cooler previously used by Brauerei Wagner in Merkendorf

Despite the near disappearance of coolships in the broader brewing industry, Franconia provided a haven for the tradition, driven by deeply rooted local pride and a commitment to brewing heritage. While many producers shifted to closed cooling systems, a small number of rural Franconian breweries simply never removed their old metal pans. Over the decades, these breweries became living testaments to older methods. When beer enthusiasts began rediscovering traditional beer styles and artisanal production methods, Franconian brewhouses that had retained their coolships found themselves lauded rather than criticized.

Coolships in Franconia today

By my latest count more than 20 coolships are still in use in Franconia on a commercial level. An example of that is Brauerei Lieberth where Christian Volkmuth employs a two-stage cooling process that bridges traditional and modern techniques. In this process, boiling wort is first pumped into a stainless steel coolship where it rests for about 30 minutes. The practical reason for the Kühlschiff is that it helps in the separation of trub (sediment) and pre-cools the wort before it goes through the plate chiller, he explains. This method is not only efficient but also adds a historical and emotional connection to the brewing process. "If we used a Whirlpool instead, we would need a completely new cooling system, which would be more complex and costly," he remarks. During this initial stage, the wort cools from near boiling to roughly 80 °C. Once this open cooling phase is complete, the wort is swiftly transferred to a plate chiller that employs a two-stage setup - the first stage uses tap water, and the second stage uses ice water—to rapidly bring the wort down to the ideal fermentation temperature for lager yeast. This setup contributes to seasonal variations in the beer, during summer, tap water temperatures range from 15°C to 18°C, while in winter, they drop to 7°C to 8°C. Consequently, the chilling process takes much longer in the summer, resulting in increased hop isomerization and a noticeably enhanced bitterness.

The coolship at Brauerei Lieberth in Hallerndorf - Courtesy of Michael Amm

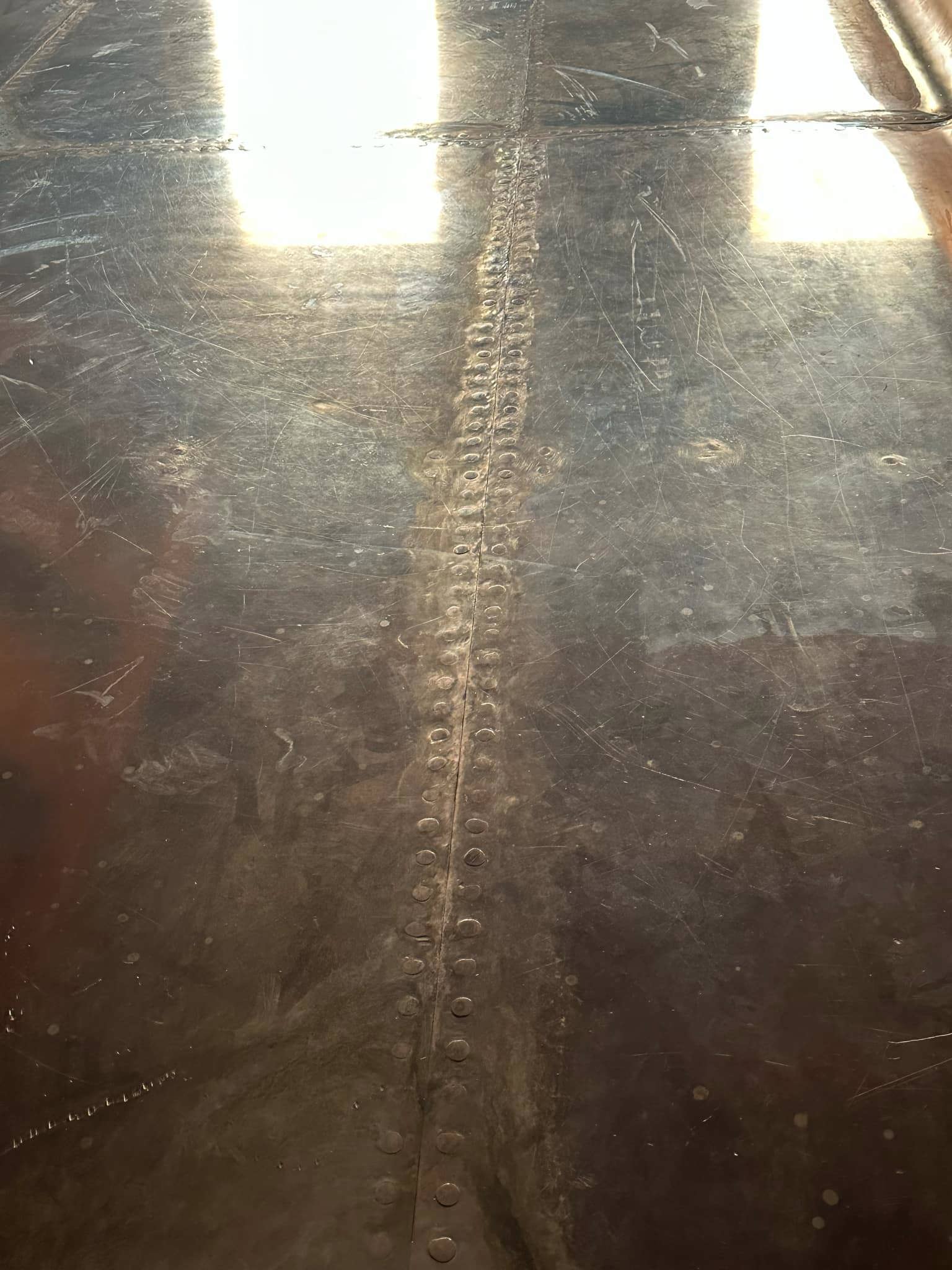

Johann Hölzlein in Lohndorf takes a similar approach. In his brewery, the wort is transferred into an exquisitely crafted coolship, where it remains for about 45 minutes. This period allows the wort to cool gradually in an open-air setting before it moves on to a secondary cooling stage. The coolship itself is a true work of art, constructed entirely from copper. Because copper cannot be welded in the traditional sense, the individual copper plates are meticulously riveted together - a technique that not only preserves the metal’s natural elegance but also upholds the integrity of a method steeped in brewing history. Or at least that is my take on it.

The coolship at Brauerei Hölzlein in Lohndorf - Courtesy of Jose Santos Caro

In Wiesen at Brauerei Thomann, they have adopted a technique where they sprinkle hops into the coolship as a late addition just before pumping the wort in, thereby capturing the desirable hop aroma without excessively increasing bitterness. While most Franconian brewers use the coolship as an initial step to cool the wort down to around 80 °C, some, such as those at Thomann, even let the wort remain in the coolship overnight during wintertime - a practice reminiscent of both Belgian Lambic and Zoigl brewers in Oberphalz.

At Grasmannsdorf Brauerei Kaiser's, Georg Kaiser is a proponent of the Slow Food movement and sees the use of a coolship as a homage to traditional, slow brewing methods that require a prolonged cooling period. He utilizes a two-step cooling process similar to Lieberth's technique, although he allows the wort to remain in the coolship for a slightly shorter duration — roughly 15 minutes. Kaiser argues that this process enhances the beer’s flavor profile: “Beers cooled in the coolship are generally milder in taste. There are several technological factors at play here; for instance, the high evaporation rate (8–10%) in the coolship efficiently removes basic and unwanted volatile aroma compounds.”

In fact, a common saying among German brewers captures the essence of this practice: "Man muss die Würze im Kühlschiff ausstinken lassen" — the wort must be allowed to naturally off-gas in the coolship.

The coolship at Brauerei Kaiser, Grasmannsdorf

The coolship at Brauerei Kaiser, Grasmannsdorf

Communal breweries in Franconia continue to uphold a rich tradition of using coolships as a central element of their brewing process. For instance, at Kommunbrauhaus Junkersdorf, a nearly 200-year-old village brew house revived by local beer enthusiasts, the coolship is used to cool the wort naturally - with hot wort manually scooped into a broad, shallow pan where significant evaporation occurs (a factor they account for when brewing extra volume). Likewise, at Kommunbrauhaus Dörflis near Königsberg, brewing is limited to the colder months so that the cast-iron coolship, operating in an open-air setting, effectively pre-cools the wort before open fermentation in wooden vessels, echoing traditional practices. Similarly, Kommunbrauhaus Unfinden close by preserves an ingenious historical cooling system. Here, brewers even once harvested winter icicles to expedite cooling in a large metal coolship.

In Neuhaus, Windischeschenbach, Mitterteich, Falkenberg and Eslarn in nearby Oberphalz, at the Zoigl Kommunbräuhäuser, they all still use a coolship. Here it remains standard practice to leave the hot wort exposed in the coolship overnight until it naturally drops to pitching temperature. Mitterteich has introduced water cooling to their coolship and Windischeschenbach has a newer variant in steel. The fact that the communal brewhouses are owned by the town or its citizens (not by a commercial brewery) helped insulate them from industrial upgrades which we can know enjoy the benefits from. Each Zoigl brew day, when the attic fills with the thick aroma of hot wort cooling slowly in the open air, you are essentially witnessing brewing history in action.

Examples of the use from other regions nearby include well-known names: Uerige and Schumacher in Düsseldorf and Augustiner Bräu in Salzburg – all of which use a coolship for all the beer they brew. At Augustiner in Salzburg, visitors can view the traditional pan where every brew is cooled the old way, a point of pride for this historic brewery. Even some monastic breweries hold on to them: at Mallersdorf Abbey in Bavaria, Sister Doris – a brewmaster nun with 50+ years of brewing under her belt – still cools her beer in an open copper coolship atop the convent brewery, singing hymns as the steam rises - what could possibly be lovelier? In my opinion, these custodians of tradition prove that coolships can coexist with modern brewing by carefully adapting (for instance, limiting exposure time or combining with a heat exchanger). Their beers, often described as particularly rounded, malty, and stable, are kept alive the notion that an open coolship could impart subtle advantages.

The coolship at Brauerei Uerige, Düsseldorf (Creditation: www.uerige.de)

The coolship at Brauerei Uerige, Düsseldorf (Creditation: www.uerige.de)

The Coolship’s Resurgence

For a long time, these few traditionalists were virtually alone. But starting in the 1990s and accelerating in the 2000s, the craft beer movement began to rekindle interest in coolships. The initial driver was not lager at all, but the allure of wild, Belgian style sour beers. Belgian lambic brewers had never abandoned coolships – indeed, they exclaim they could not make their unique spontaneously fermented ales without them. The world learned that places like Cantillon Brewery in Brussels still diligently brewed their lambics by pumping hot wort into large shallow coolships and letting them sit overnight to collect wild yeast. Cantillon’s coolship is often called a “living history” artifact – the place where lambic’s mysterious alchemy begins, inoculated by the microflora of Zenne Valley air. American and international brewers, fascinated by the complexity of lambics and gueuzes, traveled to Belgium and came back inspired. If Cantillon and a few Pajottenland farm breweries could persist with coolships and create world-class beers, why couldn’t modern brewers give it a try?

Thus, in the mid-2000s, pioneering craft brewers brought back the coolship. Allagash Brewing in Maine is widely credited as the first American craft brewery to install a coolship specifically for spontaneous fermentation, in 2007–2008. Brewmaster Rob Tod had visited Belgian lambic makers and decided to build a small shed to house an open cooling pan – a radical move at the time. Not long after, others followed: Russian River in California started coolship experiments, as did Jester King in Texas (embracing local wild yeasts), and New Glarus Brewing in Wisconsin, where Dan Carey set up a coolship to capture the native microflora. Even historic Anchor Brewing in San Francisco – which had always used shallow open coolers for its famed Steam Beer – got newfound attention (Anchor’s coolship wasn’t for sours, but it demonstrated the old method’s longevity on the West Coast). Before long, a mini “coolship craze” was underway among craft brewers, from Allagash to Anchorage (Alaska), Crooked Stave in Colorado to Wicked Weed in North Carolina – each building a vessel to harness wild fermentation or to add a twist to their brewing process. These brewers weren’t just antiquarians; they found that coolships gave their beers a sense of place, a “terroir” of local yeast and bacteria that made the flavors unique. Festivals and awards for these wild ales piled up, proving that the public had a growing thirst for the tart, funky, complex beers that coolships help create.

Happily, the coolship resurgence didn’t end at sour beers. A few craft breweries dedicated to lagers also saw merit in the old ways. We’ve already noted Jack’s Abby in Massachusetts using one for their pilot lagers, and breweries like Dovetail in Chicago (founded by two brewers trained in the German tradition) installed coolships to emulate the classic Franconian and Bohemian techniques for lager. To them, it’s about layering in authenticity and perhaps subtle differences in mouthfeel or flavor stability. As Jack’s Abby’s team put it, some brewers “feel it’s an integral part of the flavor of their beer” and worth the extra effort. In a world of ultra-clean, filtered, near-instant lagers, the slight oxidative and mineral nuances a coolship imparts might just be the secret ingredient that makes a particular lager stand out as rustic and characterful.

In brief

The history of coolships in brewing is a journey from a pioneering innovation to near obsolescence and ultimately to a thoughtful revival. Born out of the need to rapidly cool wort in a pre-refrigeration world, coolships became central to brewing operations - especially in the lager-producing regions of Franconia. They provided not only rapid cooling and natural aeration but also a means to clarify wort and strip away off-flavors. With modern technology - such as Baudelot coolers, mechanical refrigeration, and plate heat exchangers - the open coolship was largely supplanted. Yet, a few traditional brewers held on, and in recent decades, the craft beer movement has rediscovered the coolship’s unique charm.

Today, the coolship is both a cherished symbol of brewing heritage and a practical tool in select modern brewing processes. In Franconia, its legacy endures in breweries that prize tradition and flavor nuance, while around the world, innovative brewers like Brauerei Lieberth and Dovetail Brewery demonstrate that ancient methods can be harmonized with modern technology. The additional observations from local brewers—whether it’s managing slight oxidation and hop isomerization or adopting creative late hop additions - highlight that even time-honored techniques come with their own set of complexities. The coolship’s story is a testament to brewing’s continual evolution—an art and science that adapts without ever forgetting its roots.

If you haven’t already visited a brewery with a coolship, here are my highest recommendations to do so. You’ll often find that brewers are happy to show you the coolship if you ask.

Sources

- Oxford Companion to Beer, Oxford University Press 2011.

- HeadQuest Magazine, “What’s the Deal with Coolships?”, August 5, 2018

- Craft Beer & Brewing, “Exploring the Most Brewery-Rich Region in the World”, November 1, 2018

- Crafty Beer Girls (Red Rock Brewing) Blog, “Coolship Field Trip"

- Milk The Funk Wiki, “Coolship”

- Martyn Cornell (Zythophile), “Cooler vs. Coolship”

- Dovetail Brewery, Chicago

- KimLund.com, “Brauerei Lieberth”, July 2024

For more pictures of coolships, see the gallery below.